S.G.Vombatkere

Nation = People + Country + Constitution

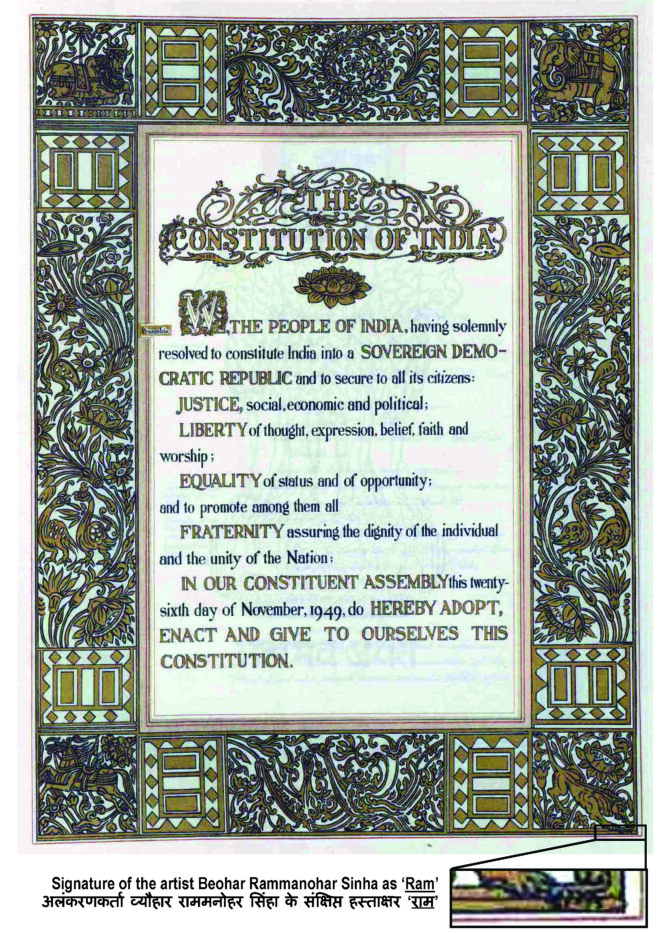

A nation is the synergetic sum of a country’s people with their social and cultural resources, who live within the boundaries of the country with its natural and economic resources, and the rules by which the people live and work. The “rule book” for India is the Constitution of India. It was the product of a solemn resolution of the people of newly-independent India. It defined Independent India as a sovereign, democratic Republic. The Constitution assures justice, liberty and equality to all India’s citizens, and exhorts them to promote fraternity, to assure dignity to individuals and the integrity of the nation.

The Constitution sets out the laws and rules according to which We the People and all the creatures of the Constitution – principally, but not limited to, the Legislature, the Executive and the Judiciary – must conduct themselves in all aspects of the affairs of the nation.

The Constitution is a living document. In keeping with changing times and circumstances, it needs to be amended without interfering with its basic structure, to suit the dynamics of societies, as the needs, wants and aspirations of the people change.

The Constitution, which was Independent India’s primary document, remains so. It directs our nation’s strategy to provide all its citizens with the primary needs of food, water, shelter, clothing, education, work, health-care and security, through the instrumentality of justice, liberty and equality. Thus the Constitution is, and must continue as, the fountain-head of all laws, codes, rules, regulations, doctrines and policies which guide the governance of the social, economic and political life of our nation.

Birth of a nation

There were many individual and joint initiatives and efforts made sequentially and in parallel, to create the document which we know as the Constitution of India, which was promulgated on 26 January 1950, the date when our Republic was “born”. It is therefore not possible to trace it from conception to birth strictly adhering to a time-line.

The leaders of our struggle for freedom from British rule and political independence, conceived the need for such a document long before Independence. Perhaps the first mention of a Constitution was by M.K.Gandhi, writing on Parliamentary Democracy in his weekly journal “Young India” dated 10 September 1931 (p.255): “I shall strive for a constitution, which will release India from all thralldom and patronage…”. The instrument with which to create a Constitution was a Constituent Assembly, a body of persons representing as wide a range of interests as possible. The formation of a Constituent Assembly was proposed in 1934. It was actually founded in November 1946, and assembled for the first time on 9 December 1946.

On 13 December 1946, Jawaharlal Nehru moved an “Objective resolution” which outlined the objectives of the Constitution. These were meant to assure to the People, the democratic trio of Justice, Liberty and Equality. To these objectives, Fraternity, was added by B.R.Ambedkar on 21 February 1948, to maintain the unity and integrity of the nation. All four are incorporated into the Preamble to the Constitution.

The 299-member Constituent Assembly comprised persons representing different backgrounds of caste, region, religion and gender. There were 166 meetings of the Constituent Assembly between 9 December 1946 and 24 January 1950, 114 of which were devoted to discussion, debate and amendment to, prepare the Final Draft Constitution of India.

At various points during the constitution-making process, the Constituent Assembly appointed a number of Committees on different aspects of the Constitution to conduct preliminary research and deliberations within smaller groups. The work of these Committees took the form of reports, which were discussed in the Constituent Assembly.

B.N Rau, who had already prepared a paper titled “Outline of a New Constitution” in January 1946, was appointed Constitutional Adviser to the Constituent Assembly. He compiled the reports of various committees to prepare a Draft Constitution which he submitted to the Drafting Committee in October 1947. It contained 243 Articles and 13 Schedules.

On 29 August 1947, the Constituent Assembly appointed a 7-member Drafting Committee from among its members. They were Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, N.Gopalaswamy Ayyangar, B.R.Ambedkar, K.M.Munshi, Mohammad Saadulla, B.L.Mitter (later resigned due to ill-health, replaced by N.Madhava Rau) and D.P.Khaitan (died in 1948, replaced by T.T.Krishnamachari). On 30 August 1947, the Drafting Committee elected B.R.Ambedkar as its Chairman.

Beginning with B.N.Rau’s first Draft, the Constituent Assembly, first under Provisional Chairman Sachidananda Sinha, and later under Chairman Rajendra Prasad, moved and debated 2,473 amendments. The Final Draft Constitution presented to the Constituent Assembly for approval, had 395 Articles and 8 Schedules. The Draft Constitution was approved on 26 November 1949. The full transcripts of the Constituent Assembly proceedings are recorded in 12 volumes.

From the status of a British colony, on Independence Day 15 August 1947, India became a British Dominion, with the Constituent Assembly functioning as its Provisional Parliament, even while continuing apace with its primary task of creating the Constitution. When the Constitution of India was promulgated on 26 January 1950, India became a sovereign Republic, finally breaking free of the British yoke.

The Constitution of India set the stage for India’s first general elections, which were held between 25 October 1951 and 21 February 1952. India’s First Parliament was constituted on 17 April 1952, and held its first session on 13 May 1952.

Selected highlights

The objectives of the Constitution are for the State to secure for all citizens: (1) Social, economic and political Justice; (2) Liberty of thought, belief, expression, faith and worship; and (3) Equality of status and of opportunity. These were based on the ‘Objectives Resolution’, drafted and moved before the Constituent Assembly by Jawaharlal Nehru on 13 December 1946. The Constituent Assembly included it in the Preamble of the Constitution.

The members of the Constituent Assembly set aside the caste and class differences which were undoubtedly present. Notable evidence of this is, the Drafting Committee consisted of five “upper caste” persons including two South Indian brahmins, one Muslim and one “untouchable” person. Merit trumping caste prejudices, they elected the “untouchable” person, B.R.Ambedkar, as its Chairman.

The Constitution is the outcome of clear-eyed determination of the members of the Constituent Assembly to sit together to create a document to build an inclusive nation. The sage advice of Provisional Chairman Sachidananda Sinha to move forward with “reasonable agreements and judicious compromises“, set the tone for debating 2,473 motions.

Jawaharlal Nehru, speaking in the Constituent Assembly, said: “The first task of this Assembly is to free India through a new constitution, to feed the starving people, and to clothe the naked masses, and to give every Indian the fullest opportunity to develop himself according to his capacity. This is certainly a great task. Look at India today. We are sitting here and there in despair in many places, and unrest in many cities. The atmosphere is surcharged with these quarrels and feuds which are called communal disturbances, and unfortunately we sometimes cannot avoid them. But at present the greatest and most important question in India is how to solve the problem of the poor and the starving. Wherever we turn, we are confronted with this problem. If we cannot solve this problem soon, all our paper constitutions will become useless and purposeless”.

The Drafting Committee obtained and studied all known Constitutions of the world, notably, those of USA, Ireland, Australia, France and Switzerland. Based upon his study of these Constitutions and the rulings of the respective Apex Courts, B.R.Ambedkar played a central role in the debates of the hundreds of suggested amendments to B.N.Rau’s First Draft.

The Draft Constitution provided safeguards for minorities. This was strongly opposed by some members of the Constituent Assembly. Defending the safeguards, B.R.Ambedkar had this to say: “In this country both the minorities and the majorities have followed a wrong path. It is wrong for the majority to deny the existence of minorities. It is equally wrong for the minorities to perpetuate themselves…. [minorities] have loyally accepted the rule of the majority, which is basically a communal majority and not a political majority”.

Regarding Fundamental Rights in the Draft Constitution, critics held that Fundamental Rights are not Fundamental Rights unless they are also absolute rights. They gave the example of the US Constitution and the American Bill of Rights, in which they believed that Fundamental Rights were not subject to limitations or exceptions. B.R.Ambedkar, with his study, grasp and understanding of the issues involved, cogently argued thus: “… it is wrong to say that Fundamental Rights in America are absolute. The difference between the position under the American Constitution and the Draft Constitution is one of form, not of substance … In support of every exception to the Fundamental Rights set out in the Draft Constitution one can refer to at least one judgment of the United States Supreme Court…”, and went on to quote a United States Supreme Court judgment in ‘Gitlow vs. New York’, which denied an absolute right to speak or publish, without responsibility.

Regarding the Draft Constitution’s inclusion of Directive Principles, critics held that they are merely pious declarations with no binding force, and should be omitted. B.R.Ambedkar argued: “I am prepared to admit that the Directive Principles have no legal force behind them. But I am not prepared to admit that they have no sort of binding force at all. Nor am I prepared to concede that they are useless because they have no binding force in law. … [T]hey are instructions to the legislature and the executive … Wherever there is grant of power in general terms for peace, order and good government, it is necessary that it should be accompanied by instructions regulating its exercise. … whoever captures power will not be free to do what he likes with it. In the exercise of it, he will have to respect these instruments of instructions which are called Directive Principles… He may not have to answer for their breach in a court of law … but he will certainly have to answer them before the electorate at election time”. The Directive Principles of State Policy were retained.

The building blocks of the Constitution

If two individuals at the core of creating the Constitution are to be named, they are B.N.Rau and B.R.Ambedkar. Both were talented, multi-faceted men of learning, with political foresight and a strong yearning for India’s nationhood. By sheer chance, the former was member of a community at the very peak of the brahminical caste system, while the latter was an “untouchable”, outside the caste system. The former started life with social, economic and educational advantage, while the latter started out without any of these and worked his way to his position of eminence.

If one can liken the Constitution to a brick structure, every brick of the structure was meticulously prepared by the Constituent Assembly. Thereafter, every brick was lifted and reverently put in place with two hands – one hand was B.N.Rau and the other hand was B.R.Ambedkar. The Constitution of India is the outcome of a labour of love, and the wisdom of our founding fathers in the sacred task of nation building.

The Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly held 166 sessions in all, and 114 of these were detailed debates focused on the text of the Draft Constitution. The balance 52 sessions were concerned with the business of the Constituent Assembly such as appointing Committees and deciding on working rules. Full transcripts of the Constituent Assembly Debates are available at <https://www.constitutionofindia.net/constitution_assembly_debates> in 12 volumes, conveniently numbered for reference or for citing by legal professionals, academics or interested laypersons.

The transcripts of the debates reveal some salient points:

# In the inaugural session of the Constituent Assembly on 9 December 1946, Provisional Chairman Sachidananda Sinha made two important observations, namely, that having a Constitution would be “… the final settlement of the problem of all problems, and the issue of all issues, namely, the political independence of India, and her economic freedom”, and that “reasonable agreements and judicious compromises are nowhere more called for than in framing a Constitution for a country like India”.

- The Constituent Assembly Chairman was Rajendra Prasad. He conducted the proceedings of the Assembly with dignity, never losing focus, and always giving full opportunity to every member within the working rules of the Assembly.

- Several members of the Constituent Assembly mention the extremely difficult political situation unfolding due to the horrific violence of Partition. They therefore urge that the work of the Constituent Assembly should proceed without delay, so that the Draft Constitution could be finalized for adoption by the Constituent Assembly.

- Members were seriously concerned about and acutely aware of the socially tense situation due to religious, linguistic and caste based differences. B.R. Ambedkar urged that the Constitution should strive towards the creation of unity among citizens by improving relations between different castes and religious communities. This is the reason for Fraternity “assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation”, finding a place in the Preamble.

- Each provision of the Draft Constitution was studied by members, who argued the implications of sentences and even particular words, and debated with well considered arguments, for their change, retention or removal. This indicated the members’ deep involvement in their onerous responsibility, their determination to produce a Constitution acceptable to all sections of opinion and interest, and their daily detailed study and hard work to prepare for the debates.

- Members with strongly opposing views argued their points passionately, but always couched in temperate language and always with dignity, respectful towards the member whom they were opposing, and accepting the decisions taken by the Chairman conducting the proceedings.

By producing a unique Constitution, the Constituent Assembly raised the status of India’s fledgling Republic on the international stage. By transacting the business of the Constituent Assembly with dignity, the members set the tone for the conduct of the First Parliament of our Republic. Our First Parliament gave India the much-needed balance, strength and stability in the crucial years immediately following the violent Partition.

Structure of the Constitution

The Constitution is our national document. It is a living, speaking document, which mandates, directs and guides the system of governance.

The ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution is its ideals, principles, spirit and philosophy, which include: (1) Supremacy of “We the People”; (2) Primacy of the Constitution and its unitary nature; (3) The sovereignty of the Nation and the State; (4) The republican, democratic, parliamentary form of government; (5) Separation of powers between the Executive, Legislature and Judiciary, the three primary branches of governance; and (6) Its federal character.

The core values of the Constitution stated in the Preamble, are: (1) Social, economic and political Justice; (2) Liberty of thought, belief, expression, faith and worship; and (3) Equality of status and of opportunity. To these are added Fraternity, which must be promoted to assure individual dignity, and the unity and integrity of the Nation. Without Fraternity, the core values lose their practical meaning.

Justice, Liberty and Equality are for the State to provide to citizens and for citizens to demand, whereas Fraternity is for the State to promote, and a duty for citizens.

The ideals, principles, spirit, philosophy and values are expressed in 448 Articles of the Constitution which are numbered serially, and logically documented into 25 Parts, each with Chapters, and 12 Schedules containing additional details pertaining to specific Articles.

The Constituent Assembly created our Constitution by selectively adopting principles from the constitutions of over 60 countries, skilfully adapting them to Indian conditions, and inserting provisions which are peculiar to India’s diversities. The continued relevance of the Constitution to changing social and economic conditions, needs and circumstances, is evidenced by the fact that during the seven decades since its first promulgation, there have been 104 amendments enacted by 17 elected Parliaments. However, in making constitutional amendments in accordance with Article 368, Parliament does not have the power to interfere with, modify, alter or change the basic structure of the Constitution.

Parts of the Constitution

The Parts of the Constitution are concerned with the following wide range of matters: Defining the extent of the Union and the formation of states within the Union; Defining the criteria for citizenship for a people in the throes of Partition; Laying down the fundamental rights and freedoms, even specifying women and children; Laying down the fundamental duties of its citizens; Laying down directive principles which are fundamental in the governance of the country and the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws; Giving equal rights to all people and universal adult franchise; Setting limitations on governments’ power, and establishing checks and balances between the organs of the Constitution; Defining three (centre, state and district) levels of government, legislature and judiciary; Defining the legislative, governance and administrative powers between the Union and the States; Setting up constitutional institutions such as an Election Commission to conduct elections, and a Finance Commission to regulate taxes and public funds.

The range of matters covered within the Constitution demonstrates the breadth of vision and the attention to detail of our founding fathers, who sat together in the Constituent Assembly. However, that has made our Constitution the world’s longest, and it has been criticized for that reason.

Criticism and comparison

The phrase “comparisons are odious” suggests that to compare two different things is unhelpful or misleading. One Jhelum Chowdhary has done precisely that. He has criticized the Indian Constitution for its length, at the 2019 World Economic Forum. He likens it to the proverbial elephant touched in different parts by blind men, each interpreting the creature in his own way, without understanding the nature of the whole. He has compared it unfavourably with the 30-times-shorter US Constitution. [“India’s constitution is 30 times longer than America’s – and still growing”; <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/india-constitution-over-30-times-long-us/>].

Although India became a Republic only in 1950, it is and has been a socio-cultural entity with a distinctive civilizational identity for over four millennia. At Independence, India was a country of amazing complexity of cultures, languages, customs, religions, ethnicities, and an ancient caste system. The large majority of India’s people lived in rural areas with a significant percentage beingforest-dwellers of many diverse tribes (adivasis). Further, the vast majority of people were economically and educationally backward. This is still true, although to a lesser extent.

The Constituent Assembly understood this complex socio-economic-cultural diversity, and was sensitive to the extremely difficult situation faced by the people at Partition. The Constituent Assembly also appreciated the needs of a new Republic, as shown by the wide range of matters in the Parts of the Constitution. Thus, although lengthy, the Constitution touches every aspect of the life of India’s people.

On the other hand, in 1767 when the American Constitution was drafted, times were different. It had less socio-cultural complexity or diversity with which to deal, since the rights of ethnic American tribes whose lands were forcibly appropriated, and of African people forcibly taken into slavery, were not even considered in its drafting. Indeed, issues such as civic rights became law only in 1964, and even today American women continue to agitate for equal rights. Additionally, each state in USA has its own Constitution, and citizens have to contend with two Constitutions. Thus, although the American Constitution is much shorter than India’s, that does not make it better.

Jhelum Chowdhary’s criticism and comparison are misplaced, and possibly indicates a lack of both knowledge and comprehension.

Understanding the Constitution

There is really no substitute for reading the Constitution to understand it, just as one may do for any subject whatsoever, even including novels. It does not require any special training to understand it, since it is logically documented and subtitled for ease of reference. It only calls for motivation to read and understand its details.

As the layperson comes across discussions and articles on constitutional and legal matters, he/she may refer to the text of the Constitution and the laws, to form his/her own understanding. The text of the Constitution and the laws in .PDF format, are readily available on the internet, free of charge.

However, on the assumption that Fundamental Rights, Fundamental Duties and Directive Principles of State Policy would interest most readers, only these are discussed briefly in succeeding paragraphs, hopefully to motivate further reading.

Fundamental rights

Part III of the Constitution assures the following fundamental rights to citizens: Right to Equality (Articles 14 to 18); Right to Freedom (Articles 19 to 22); Right against Exploitation (Articles 23 to 24); Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25 to 28); Cultural and Educational Rights (Articles 29 to 31); and Right to Constitutional Remedies (Articles 32 to 35).

Each of these broad heads of fundamental rights include other specific rights. However, fundamental rights are not absolute, and have certain restrictions or limitations. Over the years, there have been many instances of citizens seeking intervention of the Courts, to protect or restore their fundamental rights which were violated or forfeited by state or central governments.

As part of India’s constitutional history, following the Constitution coming into force on 26 January 1950, the first landmark instance of courts upholding fundamental rights, is the 14 September 1950 Madras High Court ruling in ‘V.G.Row vs. State of Madras’, upheld by the Supreme Court on 31 March 1952 in ‘State of Madras vs. V.G.Row’.

The Directive Principles of State policy

Part IV of the Constitution concerns what the State is obliged to do as a duty, in the governance of the country. Regarding the application of the principles contained in this part, Article 37 reads: “The provisions contained in this Part shall not be enforceable by any court, but the principles therein laid down are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws”. The Article directs that the principles, even though not justiciable, are fundamental in nature, and it is the duty of the State to apply them in the process of enacting laws.

The Directive Principles essentially reflect the core values of Justice, Liberty and Equality. They place a great responsibility on the State Executive and Legislature, since even though these duties cannot be enforced by a Court, the State is still obliged to do them in the interest of the people. This Part recognizes that the State has great power even while it is unaccountable in the strictly legal sense. It is only the People who can call the State to account through their representatives in Legislatures, and during elections, by changing governments.

One of the primary roles of the State Executive and Legislature is making laws. The Directive Principles of State Policy mandate that it is a fundamental duty of the State to apply these principles when making laws.

The more important of these ‘duty-principles’ are: Create a social order to promote the welfare of the people; Ensure equal justice and free legal aid; Organize village panchayats; Provide people with public assistance and the means to secure work; Provide for just and humane working conditions and maternity leave; Provide a living wage for workers; Enable the participation of workers in the management of industries and promote cooperative societies; Provide a uniform civil code; Provide for free and compulsory education for children; Promote educational and economic interests of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and other weaker sections; Treat raising the level of nutrition and improvement of public health as among its primary duties; Protect and improve the environment including safeguarding forests and wildlife.

Fundamental duties

Part IV-A of the Constitution, “Fundamental duties”, has only one Article 51-A, which reads: “It shall be the duty of every citizen of India …”, and the first duty it prescribes is, “to abide by the Constitution and respect its ideals and institutions, the National Flag and the National Anthem“. It is also a fundamental duty“to uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India“. There are nine other duties prescribed in this Article, importantly including,“to promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all the people of India transcending religious, linguistic and regional or sectional diversities; to renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women“. This is in consonance with Fraternity mentioned in the Preamble.

The fundamental duties are for every citizen of India in every walk of life. This is especially applicable to every elected representative in the States and Union Territories, and the Union government, who swears a solemn oath to “bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India” and to “faithfully discharge the duty” on assuming public office.

Conclusion

Ours is a very diverse country. It has great geo-climatic diversity – the Himalayan and trans-Himalayan mountains, the Indo-Gangetic plains, deserts, the peninsular plateau with mountain ranges, and riverine and coastal plains. People who live in different geo-climatic regions have different ways of living. They speak, eat, dress differently, and have different customs and cultures, sometimes even among co-religionists. Even within these geo-climatic regions, they may be from different ethnicities with entirely different external appearance, and be adherents of different religions. India has more than 120 languages (22 languages notified in the 8th Schedule of the Constitution) and nearly 20,000 mother-tongues or dialects.

The Constitution of India has unified these diverse communities, and is a source of strength to the people and their nation. The Constitution unifies the people through citizenship of the Union of India, making us all Indians first and foremost, regardless of our regional, linguistic, religious, ethnic, or other differences. The Constitution is the reason for the phrase “Unity in diversity” to describe India.

The Song of India is its Constitution. Its melody is Democracy. The lyrics of the song are about Justice, Liberty, and Equality for all its diverse people. Fraternity among all the people of this proud nation provides the harmony.

It behoves every Indian to make efforts to read and understand the Constitution in his/her own way. This article will hopefully serve as an introduction to enthuse readers to make a more careful reading of our nation’s primary document.

Jai Hind!

Reproduced from Countercurrents.org with the author's permission. S.G.Vombatkere is an Indian Army Veteran who retired in the rank of Major General in 1996, after 35 years in uniform, from the post of Addl DG (Discipline & Vigilance) in Army HQ.

One cannot help but be struck by the difference in tone and substance between the ethos expressed in the Constitution and that being noised about oftentimes nowadays. Indeed, with the palpable shrinking of space for public discourse, the media, it is difficult to hear much at all, above the noise.

Perhaps the greatest of all dichotomies lies in the section expressing the duties that bind all India’s people: Article 51A, (a) to abide by the Constitution and respect its ideals and institutions, the National Flag and the National Anthem; (b) to cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national struggle for freedom; (c) to uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India; (d) to defend the country and render national service when called upon to do so; (e) to promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all the people of India transcending religious, linguistic and regional or sectional diversities; to renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women; (f) to value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture; (g) to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures; (h) to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform; (i) to safeguard public property and to abjure violence; (j) to strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective activity so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels of endeavour and achievement; (k) who is a parent or guardian to provide opportunities for education to his child or, as the case may be, ward between the age of six and fourteen years.

Rather than any of this, we have the spectacle of a Union Cabinet Minister celebrating, publicly, ‘teaching a lesson’ – a reign of terror (marked unambiguously as being masterminded, yet judicially indeterminate, leaving him free to take credit without fear of the long arm of the law), that left thousands dead, but which continues to win elections on the promise of widening social and economic divides [clauses (b), (c), (e) and (i)]. We have ‘developmental agendas’ promoted on the premise of irreversible destruction of pristine natural flora and fauna [clauses (g) and (h)].

All this and more, while being reminded ad nauseam of the importance of the citizen’s duties towards the state.

We also have a Parliament that is overwhelmingly partisan, and using this imbalance to accelerate the passage of Bills that in letter and spirit strike down the Fundamental Rights promised in Part III. Such laws enable the creation of subsidiary Rules that effectively deprive the citizenry permanently of the benefits of such Rights, making a mockery of the ‘limits’ implicit in the exercise of Fundamental Rights, without, however, expressly delineating such breach or breaches of limits. Rather, it is becoming a practice to facilely brush over such breaches, under the cover of creating important laws to regulate business and commerce in a fast-changing technological and economic global environment.

Undoing such changes will be a massive problem in any future political scenario, even one that is as overwhelmingly numerical, but is characterised by the sort of liberal and Constitutional outlook that is so plainly missing now.

Looked at with the impressive wisdom of hindsight, the lofty aspirations expressed in the manner by which the Indian Constitution is detailed are remarkably straightforward to undermine, as long as a majoritarian party has control of a significant number of seats in both Houses of Parliament.

An important article which traces the evolution of the Constitution from the formation of the Constituent Assembly to the date on which India became a sovereign democratic republic. Essential reading for all citizens.